The Chaldean Godfather, Detroit Free Press, April 25, 1988

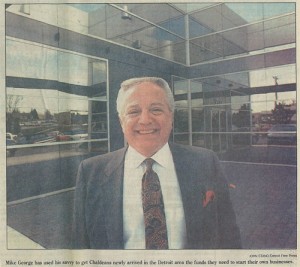

Loyalty and family ties boosted Mike George’s commitment to helping immigrants get settled Mike George the Detroit-born son of a Chaldean farmer, heads Melody Farms, one of Michigan’s largest dairies. In a low profile way, he is also the chief financial supporter of the Chaldeans who run most of Detroit’s party stores.

Loyalty and family ties boosted Mike George’s commitment to helping immigrants get settled Mike George the Detroit-born son of a Chaldean farmer, heads Melody Farms, one of Michigan’s largest dairies. In a low profile way, he is also the chief financial supporter of the Chaldeans who run most of Detroit’s party stores.

At the end of World War II, there were fewer than 100 Chaldean families in metro Detroit. Those few prospered by running small groceries. Relatives invited relatives from the old country, and the chain lengthened.

Today there are perhaps 50,000 Chaldeans — Catholic Iraqis from near Baghdad — living in the area.

And virtually all of them are beholden to Mike George.

“He’s known as the godfather in the Chaldean community,” says longtime acquaintance Edward Deeb, president of the Michigan Food and Beverage Association, a trade group.

At 55, George heads Melody Farms, one of Michigan’s largest dairies, supplying milk, ice cream and other products to stores. In a low-profile way, he is also the chief financial supporter of the Chaldeans, who run most of the grocery-convenience party stores.

And, over the last several years, George has quietly become a real estate developer to be reckoned with. He and his partners have built major office buildings along Northwestern Highway in Farmington Hills and flanking I-275 in Livonia. Increasingly, he dabbles in small hotels and retailing.

Today, the dreams are getting grander. Should financing and tenants fall into place, George plans to develop 23 acres near the Renaissance Center along the Detroit River into office and residential towers. George admits the project is ambitious, even visionary, and he knows the odds against succeeding in full are long.

But, in the years since he “barely finished” high school in Detroit, this son of a Chaldean farmer has succeeded more often than he has failed.

Family ties are strong among Chaldeans, says Joseph Sarafa, George’s nephew and executive director of the Associated Food Dealers of Michigan, another trade group. Sarafa recalls that when he was struggling at the University of Detroit School of Law and working full-time in his own party store, George showed up one day and took him to the London Chop House, one of Detroit’s premiere restaurants. It wasn’t a grandiose gesture, merely a boost from one family member to another, Sarafa says.

There are probably 1,500 Chaldean stores in the Detroit area, estimates Deeb. That translates into more than a third of all groceries and party stores in the tri-county area. In the early years, George used his own growing fortune to bankroll newly arrived Chaldeans.

When that became cumbersome, he formed Metro Detroit Investment Co. in 1978. The firm is a funnel for loans from the U.S. Small Business Administration to minority business owners. The SBA and other lenders rely heavily on George’s knowledge of the Chaldeans.

“We look at their character first,” says George, explaining that he judges a newly arrived countryman largely by the family. If the family is of decent character, the nod is given and the loan is approved. Hundreds of Chaldeans have gotten started through George’s efforts. Records show the loans that pass through Metro Detroit range from a modest $15,000 or so to substantial financing of $350,000 or more.

George shrugs when a visitor suggests that he is enormously influential among the Chaldeans. “Who’s going to put them in business?” he asks, if not someone more fortunate than they. George’s father, Tom George (1900-1958) emigrated from Iraq in 1929, coming to Detroit for a job in the auto industry. But he couldn’t read or write English, so he didn’t get a job. “I always say it’s the best thing that ever happened to a lot of people,” son Mike says. True to the immigrants’ creed, he believes that a privileged birth is more hindrance than help.

Undeterred, Tom George, a farmer back home, opened a small grocery at John R and Vernor. Mike was born in 1932 in Detroit, and grew up in his father’s store.

Once when Mike was 11, his parents went to New York to welcome friends. “My dad told me, ‘Don’t touch anything,’ ” George recalls. But a large shipment of canned goods arrived, so the youngster shoved everything around in the storage shelves and put away the goods. On Monday, his father was fuming. Unable to read, he had stocked the various Campbell soups each in his own niche, so he could tell which can to reach for when customers asked for it. With the filing system awry, Monday was chaos. “I embarrassed him,” George recalls. “He made me stay up all night, moving everything back where it belonged.”

It’s still difficult for George to keep his hands off everything. Around 1980, he recalls, his bankers told him they wanted him to take out a $5 million life insurance policy on himself because he was so intimately involved in each business that his loss would be devastating. “I became insulted, but after I thought about it I realized they were right,” he says. So he brought in some professional staff, relinquished some of the hands-on control and now spends most of his time lining up new deals and solving problems.

That still keeps him carrying two briefcases of work when he leaves the office. His hobbies include boating and cigars, but he finds little time for the first and his family and office workers nag him about the second.

George serves on numerous civic groups, including Detroit Mayor Coleman Young’s casino gambling study commission, but he privately dislikes the time taken away from his work and family. He knows the political scene in Lansing and takes a keen — if backstage — interest in legislative issues of concern to his industry, such as cutting red tape involved in licensing stores to sell liquor. A private man, George shunned interviews until his Detroit riverfront proposals forced him to deal with reporters. “Deep down, I just don’t like to do these things,” he says. “I really don’t like to be in the limelight.”

After George slipped through high school, college was out of the question. Besides, he wanted to work in the family business. His older brother, Sharkey, born in Iraq, is his partner and remains chairman of the firm today but does not take an active part in the day to day operations. The family had a milk route.”My dad always told me to stay in a business where people will consume the product regardless of the economic conditions,” George says. So, after a hitch in the Army, George and his brother gradually built up the milk route, serving as a distributor for milk and ice cream.

For a long time the business prospered in a small way. It was incorporating as Melody Farms in 1962 even as the family ran it out of a converted dining room. Eventually they switched from distributing others’ products to producing their own. And Melody Farms gradually added capacity, buying one bankrupt dairy here, taking over another producer there.

The company did $10 million in business in 1978, $30 million in 1981, $93 million last year and probably will top $100 million this year, George says. “There’s room to grow,” he says. The company, still focused on Michigan, is cautiously venturing into parts of Ohio and Indiana. His personal holdings make him worth around $10 million, according to sources.

George got into real estate development almost by accident. Initially he helped bankroll his cousin, Jim Jonna, who in the 1970s ran a construction firm. In the 1981-82 recession, they needed space for themselves, so they and their brothers built the office building at 30777 Northwestern Highway in Farmington Hills where George has his office.

There was never a sign out front to advertise space for rent. “The number of people who came to rent just blew our mind,” George says. So the Georges and the Jonnas bought 10 acres across the street and threw up two more buildings called North Valley, tapping into the suburban office boom of the ’80s. “Our success was immediate,” he says. Another building nearby followed, called Wellington North.

Steve Morris, a partner in the real estate brokerage firm of Morris & Moon, says the Jonna-George team quickly got a reputation for well-conceived, quality projects. “Today they would be considered one of the top five developers of office property in metropolitan Detroit,” Morris says. Previously, George was mostly a passive investor, but he has become more active. With various partners, he opened a small hotel under the name Compri at the Los Angeles International Airport. He’s building two more Compri hotels, one in Southfield and one in Livonia. Aimed at the business traveler, the hotels hold nightly rates to under $100 by eliminating food and banquet service. George bought 35 acres in Farmington Hills and sold it to the Michigan National Bank, which is building its headquarters there. He plans a pair of suburban office buildings in Southfield, both joint ventures with the tenants, a health care company and an accounting firm. And he is involved in the Chestnut Hills office development near Eight Mile and I-275, including plans for two office buildings with 500,000 square feet of space.

His name has become better known as a result of Amerivest, a venture he formed in 1985 with developer Brian Palmer.

Their most ambitious proposal is for the Detroit riverfront. That calls for two office towers, two luxury apartment buildings and a parking garage.

George says he won’t proceed with the first office tower unless it is 30 percent leased. But he is confident. And he promises that the apartment towers will be “much more luxurious” than anything now on the river. “Our rents will probably run somewhere between $1,300 and $3,000,” he says, assured he’ll find the tenants will to pay such steep prices.

Not all his ventures have been success stories. There was the time he thought he saw a need for a firm that would operate a safety deposit vault. Typically, the idea came to him because he couldn’t find a nearby vault for his own needs. So he formed another company, dug a basement in one of his office buildings on Northwestern Highway, installed 24-inch thick walls, and waited in vain for customers.

“Nobody wants to deposit with us,” he explains. He grasped, too late, that people trust banks with their valuables but not private firms. “Very simple point, but we ignored it,” he says. With the vaults all but empty, he converted the firm to one that stores backup computer tapes for companies and has done very well with it.

And then there were the restaurant flops. A Middle Eastern restaurant in Southfield was a disaster. George reached his limit one night when, short of help, he donned an apron over his business suit and began washing dishes. A client waiting for him wandered into the kitchen, spotted George and said, “I knew that you were anxious to make a lot of money, but I didn’t know you would resort to dishwashing.”

Mike George is a very happy ex-restaurateur.

MIKE GEORGE

* JOB: Runs Melody Farms, one of Michigan’s leading dairies; developer of hotel, commercial office projects.

* PERSONAL: 55; wife, Najat; six sons; lifelong Detroit area resident.

* HOBBIES: Cigars, boating and fishing

* WEALTH: Sources estimate George’s business and real estate holdings are worth $10 million.